It’s a simple concept really. The oyster industry is not producing enough larvae to meet the demand in the marketplace, and Ferry Cove Shellfish intends to plug this hole in the supply chain.

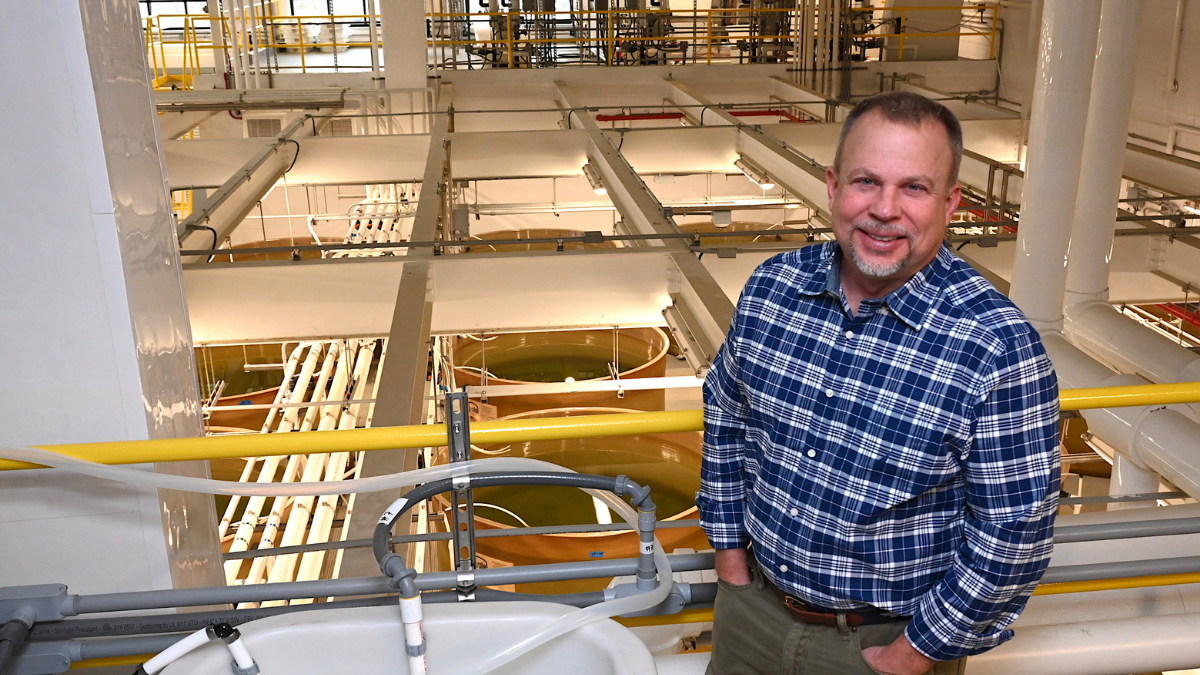

When fully functional, this new, state-of-the-art facility in Sherwood, just a stone’s throw from the Chesapeake Bay, is poised to become one of the largest oyster hatcheries on the East Coast. The mission: sell oyster larvae to commercial growers, thereby increasing oyster production and feeding the hungry oyster market.

Of course, if it were that easy, a hatchery might be on every corner.

“Hatcheries are expensive to operate and the return on investment is low,” says Stephan Abel, Ferry Cove’s president and CEO. “To break even and make money, you’ve got to produce a high volume.”

One look at the modern industrial complex tells you the company is planning to do just that. Ferry Cove Shellfish is using cutting-edge technology and the latest scientific discoveries to maximize efficiencies and lengthen the growing season. This will increase the number of larvae they can produce and sell over the growing season.

An entrepreneurial approach to producing oyster larvae is unique and has yet to be proven to work on a commercial scale, but Abel is confident. “There are other hatcheries doing similar things, but we are definitely pushing the envelope in terms of marrying proven hatchery husbandry with technology.”

Pushing the Envelope

A Navy veteran and lifelong sailor, Abel was introduced to the Chesapeake Bay — and the environmental programs designed to benefit it — while working at the Maryland Department of Natural Resources. After that, he served as executive director of the Oyster Recovery Partnership, a nonprofit organization focused on large-scale oyster restoration and sustainable fisheries management strategies.

When Maryland’s oyster regulations changed a few years ago, Abel says two things became apparent. Aquaculture was a growing industry, and those who leased bottom in the Chesapeake Bay were going to need to “use it or lose it.” Growers can lease an acre of bottom for $3.50, but waiting for a “natural strike” is economic roulette.

“The Bay hasn’t seen the natural spat sets it once did” Abel explains. “It used to be a lot higher. That’s not to say that the Bay doesn’t get natural strike. Last year was a phenomenal strike. But if you have leased bottom, just waiting for natural strike is not good enough. You’ve got to do more.”

Doing more means planting more oysters. Consequently, more oyster larvae are needed when growers with leased bottom take a more active role in production. Add in the restoration efforts in both sanctuaries and public fishery reefs, and you can quickly do the math. Demand exceeds capacity.

Preparation and opportunity came together for Abel when he began working with the Phillip E. & Carol R. Ratcliffe Foundation. He built a relationship with the Annapolis-based organization while still with the Oyster Recovery Partnership. As his idea for an innovative hatchery project began to take shape, he shared it with his contacts at the foundation.

“I originally approached them about a training program to assist watermen in producing their own oysters to give them a supplement income beyond the wild fishery,” Abel says. “The foundation agreed to underwrite a feasibility study.”

The study confirmed what Abel and others in the industry already knew. There is, indeed, a shortage of oyster larvae, and it would be costly, though not impossible, to build a new facility from the ground up. As a result, the Ratcliffe Foundation agreed to fund the purchase of the property and the construction costs for the new facility.

A Home in Talbot County

When looking for the perfect spot to plant the hatchery, Abel and his backers evaluated a number of parcels, gauging water quality, salinity, and access to talent. In the end, the 70-acre Sherwood property came out on top. The foundation closed the deal in 2019, and Abel formed a nonprofit to operate the facility.

“It’s a good location for us,” Abel says. “It married good water quality and available land. Historically speaking, the good oyster reefs have always been on the Eastern Shore. The saltier water comes up the Eastern Shore so you always get good flow here.”

Talbot County’s proximity to urban areas and institutions of higher learning added to its appeal. A ready stream of highly qualified tech workers is necessary for an enterprise such as this to be successful. “Most of the staff here are young,” Abel notes. “This is an emerging industry. A few years ago, working in a hatchery wasn’t even an option or a career path.”

Structuring the business as a nonprofit makes sense for this project, as well. Though the core business will be the production of larvae, seed, and potentially spat on shell, building partnerships within the industry is going to be important.

“There is a lot yet to be done in terms of supporting the industry, educating the industry, growing the industry,” he explains. “Establishing the nonprofit gives us the ability to do research if we need to, but also allows us to apply known science in a very large way.”

Production Begins

Crassostrea virginica, better known in these parts as the Chesapeake Bay oyster, grows along the eastern coast of North America, from the maritime provinces of Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. A single oyster can produce up to a million viable larvae.

Ferry Cove is already taking orders for spring delivery and the hatchery is a hive of activity as workers make preparations to begin production. Oysters typically spawn in June, July, and August. But with the right water temperature and food sources, the hatchery can mimic summer conditions, extending the spawning season to March through September.

“The whole point of the hatchery is that you are trying to simulate Mother Nature’s natural reproduction cycle,” Abel explains. “You trick the oysters into thinking that it’s summertime.”

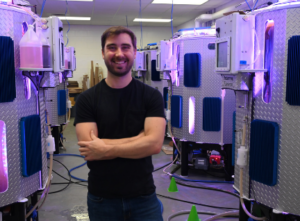

The water comes right out of the Chesapeake Bay and runs through a complex filtering system that can control water conditions from salinity to temperature and beyond. Technology also allows biologists to grow an endless supply of algae in very high concentrations, which they then use to create a balanced diet to feed the spawning bivalves.

Computers that can detect even the slightest change in the growing tanks, and managers receive a notification instantly if a problem arises. Hatchery manager Steven Weschler has an app on his phone that allows him to tap into any system remotely when needed. If an alarm goes off in the middle of the night, he knows it.

Technology even helps control production costs.

“The most expensive things in this enterprise are people followed by utilities,” Abel explains. “If you can use technology to reduce your needs for monitoring, then you cut down on the number of people you need. If you can be highly efficient in your heating and cooling systems, then you save money. We’ve simply leveraged the latest systems and applied them on a production scale.”

As production shifts into high gear, Abel predicts that Ferry Cove Shellfish will spawn other business development. From setting facilities to additional growers and packing houses to truck drivers, the economic ripple will be felt throughout the region.

“It’s like starting the engine,” Abel says. “You have more larvae, more oysters, more harvest. We know there is demand, so it just kind of snowballs. More oysters in the Bay are good for everybody.”

Ferry Cove Shellfish is located at 21770 Lowes Wharf Road in Sherwood. For more information, visit ferrycove.org.

Never miss an update: Sign up for Talbot County Economic Development and Tourism’s Talbot Works newsletter here.